Adobe in West Texas

Adobe is an ancient building material created by combining clay, water, sand, and grass or straw. The mixture dries and hardens in the sun, making it ideal for arid climates. In the American Southwest, adobe architecture evolved from the fusion of Indigenous and Spanish building traditions. The Pueblo people began building with adobe as early as 900 AD, employing a method known as ‘puddled adobe,’ in which layers of soft clay were hand-molded into place. Spanish colonists in the 16th century introduced new techniques, including the use of wooden molds to efficiently produce uniform adobe bricks that could be stacked and held together with mud mortar. They also applied lime stucco or mud plaster over the bricks for a smooth protective finish, and introduced metal tools for crafting wooden vigas, corbels, and lintels.

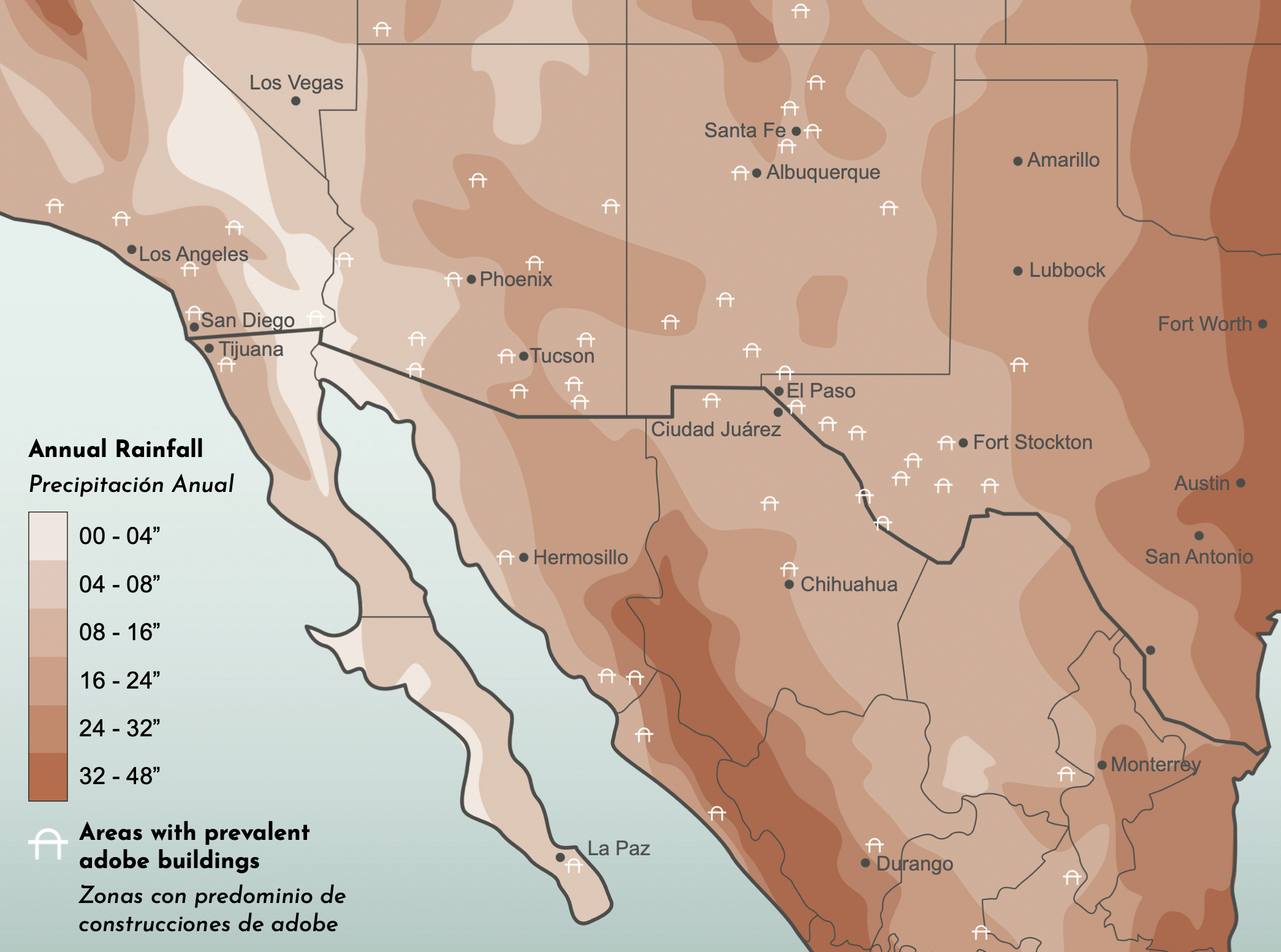

Map demonstrating the correlation between average annual rainfall and adobe construction in the Southwestern United States and Northern Mexico. Areas with drier climates have a higher prevalence of adobe buildings.

EVOLUTION OF ADOBE ARCHITECTURE

In the 1680s, Spanish missionaries established several adobe churches and missions in present-day El Paso County, including those at Ysleta and Socorro. The missions influenced residential architecture in nearby settlements, leading to the proliferation of adobe homes. The Colonial Style, popular at the time, was characterized by a rectilinear floor plan with rooms arranged around a central courtyard. Exteriors were simple, often featuring wooden lintels above doors and windows.

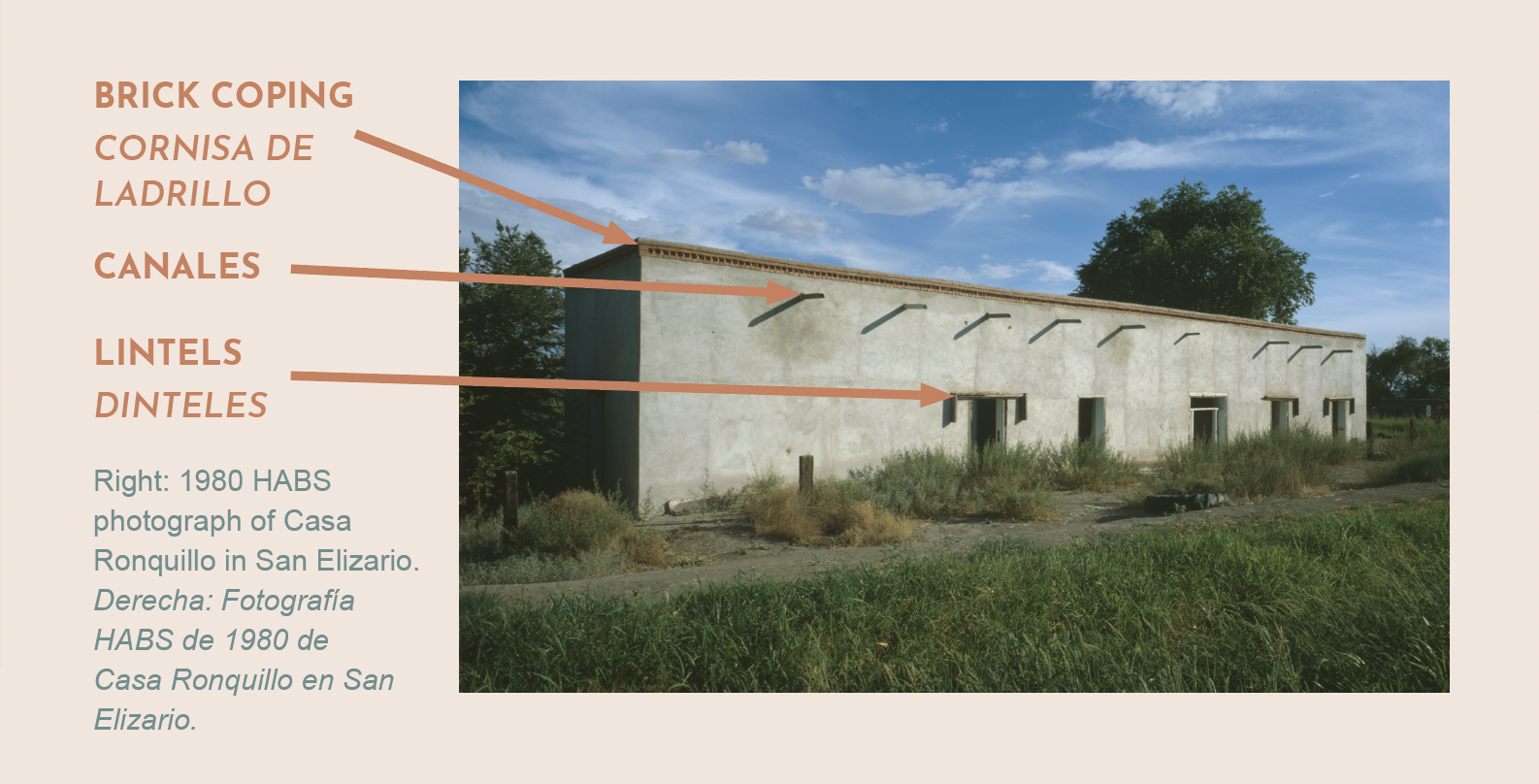

As settlement in West Texas increased after 1848, the region saw the rise of the Territorial Style, a blend of Spanish colonial and Eastern U.S. architectural elements. This style was characterized by brick accents designed to imitate Greek Revival-style architectural elements, such as decorative coping. Casa Ronquillo in San Elizario is a notable example of the Territorial Style.

With the arrival of the railroad in 1881, new construction materials imported by train such as brick, limestone, cast-iron, corrugated tin, factory-produced wood, and reinforced concrete began replacing adobe in El Paso County. In 1907, Portland cement was introduced to the region and began being used in place of traditional mud or lime plaster to clad adobe structures. Unfortunately, this impermeable material traps moisture and causes damage to the adobe beneath. Despite these challenges, adobe remains a significant part of the architectural heritage of El Paso and the Mission Valley. While adobe buildings are rapidly disappearing, the techniques for constructing and repairing adobe structures can be revived.

THE FUTURE OF ADOBE IN WEST TEXAS

In recent decades, there has been a renewed interest in adobe construction, preservation, and its potential to support a sustainable heritage tourism economy. Since the 1960s, a series of books has promoted adobe building for its efficiency and environmentally friendly methods. More recently, organizations such as Cornerstones and the Earthbuilders Guild in New Mexico, the National Park Service, and Preservation Texas have offered hands-on training programs and educational resources to encourage adobe conservation.

Since 2004, Preservation Texas has added several West Texas adobe structures to its annual list of the state’s most endangered places. Among these sites are Old Fort Bliss in El Paso, the Socorro Mission Rectory and Rio Vista Farm in Socorro, the ‘Oldest House’ and Winfield Hangar in Fort Stockton, the Sacred Heart Church in Ruidosa, and the Scobee Adobe House in Fort Davis. While the Socorro Mission Rectory and Scobee Adobe House have benefited from successful preservation efforts, many other adobe buildings remain at risk. Fortunately, there are several mechanisms available to support the preservation of these structures. Properties that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places are eligible for tax credits to aid in their restoration. To ensure the survival of publicly-owned adobe buildings, stakeholders must take advantage of preservation resources, such as grants and tax incentives, and volunteer skills training to sustain adobe construction into the future.

Participants at a 2024 adobe workshop in El Paso facilitated by Preservation Texas learned how to create adobe bricks and repair damage to adobe structures.